|

| Scopes Trial |

Often known as the "Monkey Trial," this face-off between free speech and state educational prerogatives pitted "modern" science against "old-time" religion. A major fault line in U.S. society was exposed when two of the United States' most famous figures—lawyer Clarence Darrow and three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan—clashed in the tiny town of Dayton, Tennessee.

Although Charles Darwin's theory of evolution had been provoking controversy since 1859, not until the post-progressive 1920s did five states, including Tennessee, legislate how, or even whether, evolution could be taught in taxpayer-funded public schools.

The actual legitimacy of evolution was not at first the main issue. Rather, the recently formed American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) challenged Tennessee's new law as a violation of free speech. A test case required a defendant, and that role was pressed on 24-year-old John Thomas Scopes (1900–70), a math teacher and football coach at Dayton's high school.

|

Substituting for an absent biology teacher, Scopes had read a passage on evolution to his class from a textbook formerly approved for use in Tennessee. Scopes clearly had violated the new state law, but what did that mean? More than 100 reporters, including Baltimore Sun gadfly H. L. Mencken, converged on Dayton for an eight-day July trial to answer that question. The proceedings were carried nationally on radio.

The four-man defense, led by Darrow, sought a broad discussion of free speech and scientific authority; the prosecution's aims were less clear. Bryan, assisted by his son, Will Jr., knew that Scopes had broken the law, but he also wanted a chance to defend religious beliefs against godless modernism, including what he saw as the unacceptable Social Darwinist idea that the weak be allowed to fall by the wayside.

Presiding Judge John T. Raulston allowed only one of the ACLU's scientific experts to testify. He found Scopes guilty before allowing Darrow's and Bryan's plea for closing arguments, during which both hoped to make their larger cases to a national audience.

|

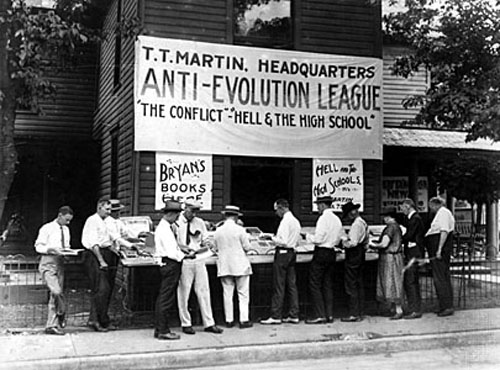

| anti evolution league |

On Monday, July 20, 3,000 people were on hand to hear the debate on the lawn outside the hot, cramped courthouse. Darrow, an admitted agnostic and skilled litigator, peppered Bryan with questions regarding the literal truth of the Bible. Bryan was the finest public speaker of his generation, but he was no theologian and seemed poorly prepared. His defense of the Bible was feeble and often laughable.

Although Judge Raulston expunged Bryan's testimony from the court record, millions had heard it via the media. Mencken's newspaper paid Scopes's $100 fine. (His conviction was later voided on a technicality and never refiled.) Six days later Bryan died in Dayton of diabetes.

The Monkey Trial revealed how hard it was for urban secularists and rural believers to find common ground. In 1955 a lightly fictionalized courtroom drama, Inherit the Wind, introduced this "trial of the century" to new generations as a huge victory for science. It was, but it also was not. Tennessee repealed its statute in 1967. But controversy over evolution would reemerge as religious Protestants and others began expressing themselves more forcibly in school, state, and national politics.