|

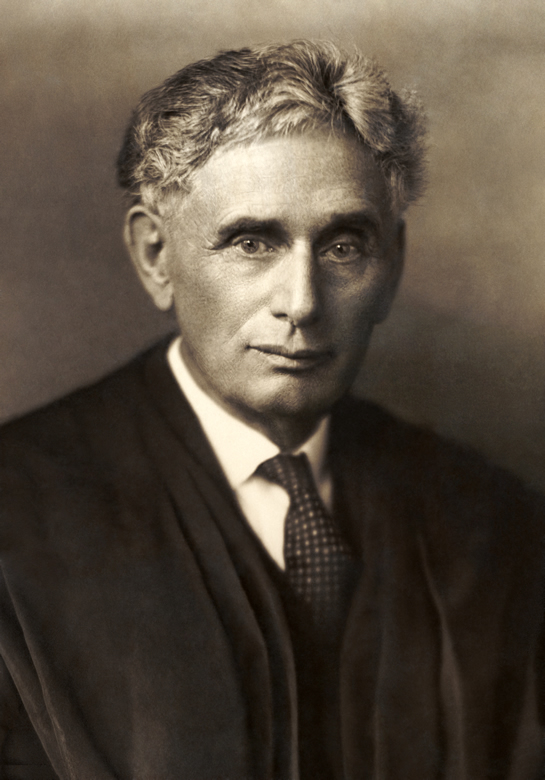

| Louis D. Brandeis |

A son of German immigrants who became a crusading attorney and the United States' first Jewish Supreme Court justice, Louis Brandeis made his mark as a leading progressive and helped shape President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal.

Brandeis was born in St. Louis but made Boston his home soon after graduating from Harvard University. He became a wealthy lawyer while also pursuing cases on behalf of embattled labor unions, immigrants, and others left behind in Gilded Age America. He took on streetcar and railroad interests and wrote muckraking articles about banking.

In 1910 New York City cloakmakers struck local sweatshops. Brandeis negotiated a settlement satisfactory to both the International Ladies' Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) and the manufacturers.

|

Brandeis believed that big business tended to excessively concentrate economic power, harming regional and local enterprises and eliminating true competition. He played a key role in making the Constitution's Fourteenth Amendment, used mostly to bolster corporate rights since its adoption in 1868, into a vehicle expanding rights for ordinary people.

His biggest victory came in 1908 when in Muller v. Oregon the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the state could prevent manufacturers from making women work more than 10 hours a day. Brandeis's win came just three years after the Court had invalidated a maximum hours statute for bakery workers.

In what was soon nicknamed a "Brandeis Brief," its namesake wrote a 112-page document that went far beyond narrow legal precepts, adding sociological information that, in the words of the Muller decision, included "extracts from over ninety reports of committees, bureaus of statistics, commissioners of hygiene, inspectors of factories, both in this country and in Europe, to the effect that long hours of labor are dangerous for women...."

By the time President Woodrow Wilson nominated Brandeis, a political ally, to the Supreme Court, Brandeis had a national reputation as "the people's attorney." Nevertheless, his confirmation process was difficult. Both his liberalism and his religion were held against him. His "fitness" was questioned by leading attorneys, including former President William Howard Taft, and officials from his alma mater opposed him. Brandeis was confirmed by a 47-22 Senate vote in 1916.

Considered a reliably liberal member of a rather conservative court, Brandeis was a supporter of the New Deal but by no means a doormat. In 1935 he joined in the unanimous Schechter decision that killed Roosevelt's National Industrial Recovery Act, a centerpiece of the New Deal program. In 1932 Benjamin N. Cardozo joined the Court as its second justice of Jewish descent.

Brandeis was instrumental in mentoring Felix Frankfurter, a law professor and Roosevelt aide, who became the third Jewish member of the Court, replacing Cardozo when he died in 1938. Brandeis, who was 80 when Roosevelt proposed his controversial 1937 Court-packing plan, was offended but decided to retire in 1939.

Brandeis was not especially religiously observant but took a strong interest in Zionism during World War II. His Court duties and a falling-out with European Zionists, including Chaim Weizmann, reduced his involvement, but Brandeis continued to back creation of a Jewish state in British Palestine. In 1948, seven years after Brandeis's death and the year of Israel's founding, Brandeis University opened in Waltham, Massachusetts, commemorating its namesake as a Jewish-American legal pioneer and supporter of social justice.